Welcome to our Musical Zodiac, in which we arbitrarily match instruments to personality types and use that as an excuse to discuss our favorite musickers. Aquarius runs from 20 January to 18 February, and the sign is supposed to be “known for being compassionate, independent, and rebellious” - which says “saxophone” to me!

Somewhere there's music

How faint the tune

Somewhere there's heaven

How high the moon

“How High the Moon” was written in 1940 and quickly entered the standard American songbook, to be covered and reimagined countless times by dozens of artists. This version features Sarah Vaughan singing and Cannonball Adderley on saxophone:

This is one of those songs that I’ve come to use as a “test case” for artists I don’t already know. It’s a song I already know intimately, having performed an arrangement in high school, and whenever I encounter it being covered by someone else, I’ll give it a listen to see what sort of artist they are.

Hearing Sarah Vaughan perform this song gave me some insights into the sorts of choices she makes as a singer, and made me want to hear more of her. If, like me, you were already familiar with Ella Fitzgerald, it might be difficult to approach another jazz singer without comparing them. Using a song like “How High the Moon” can be a good way to work your way into Vaughan’s catalog.

Then I looked at the liner notes because there was something familiar about that saxophonist, swapping licks with Sarah’s scat singing in the back half of the recording.

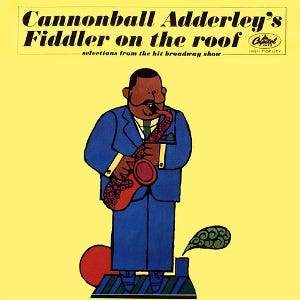

Julian Edwin “Cannonball” Adderley was a creative force I might never have noticed if it weren’t for Fiddler on the Roof. Adderley saw that show in 1964 and immediately went into the studio with his younger brother, Nat, on trumpet, keyboardist Joe Zawinul, fellow sax player Charles Lloyd, and a rhythm section of Sam Jones (bass) and Louis Hayes (drums) to put out his version.

I found a copy of Adderley’s Fiddler at the library, not long after seeing the film version of the show on TV, and that cover art caught my eye. The combination of Beatles’esque artwork and the set of familiar songs provoked my curiosity, and after a few listens, I was hooked.

There is one particular moment that I remember, as trumpeter Nat carried the melody line on the second track, “To Life”—I tried to learn how to duplicate this “smear” effect on my own, and never quite nailed it:

Long-time readers might remember that Freddie Hubbard’s appearance on Billy Joel’s “Zanzibar” was what initially drew my attention to jazz:

It was Nat Adderley’s trumpet playing on this record that pulled my attention to his big brother’s project and compelled me to listen to it multiple times. I was still an inexperienced and self-centered youth, so it took another trumpet player to draw my attention to the wider world of the saxophone in jazz.

Cannonball Adderley became one of those names I would look for when I was exploring the jazz section of the record store. He became one of those familiar names I could count on to deliver music that would challenge and satisfy me. To find my way to him I had to be open to the unfamiliar, but I got there through familiar songs, familiar names, and small progressions from the familiar to the new.

Along the way, I was developing a sense of musical vocabulary. Armed with that, I could understand more of the unspoken language of music and hear what artists were trying to tell me with their songs.

Only after listening to Cannonball Adderley for years and years did I finally come around to a fuller appreciation of John Coltrane…but that’s a longer story for another day.